Fusion or Fission: A comparison between China and U.S. Vertical E-commerce Markets

In the two biggest economies, vertical e-commerce markets are going through completely different transformations.

by Azoya

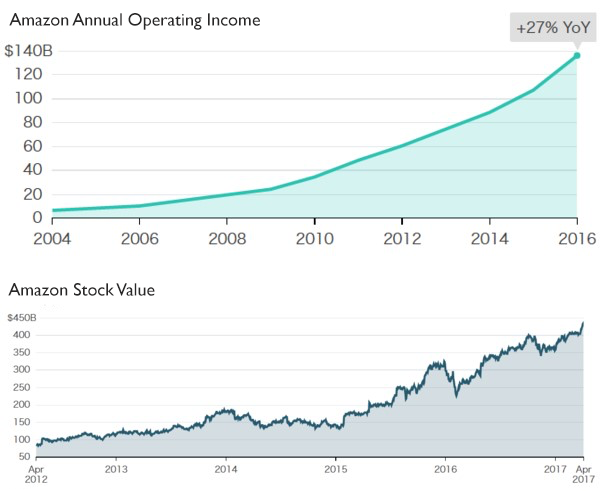

Over the past two years, the U.S. vertical e-commerce market has been in a new round of mergers and acquisitions. We are witnessing share value of Amazon doubling for two consecutive years, rendering current market value at least three times higher than in 2014.

Conversely, China's e-commerce market is in the ‘fission’ state. Expansion of Tmall and Taobao in domestic market is slumping. However, Chinese vertical e-commerce markets, such as cross-border e-commerce imports are seeing exploding number of vendors, which can be attributed to Chinese consumers’ acceptance of B2C models.

In the two biggest economies, vertical e-commerce markets are going through completely different transformations. In the U.S., big e-commerce groups such as Amazon and Walmart are sweeping the industry with the help of funds, technologies and innovation.

At the beginning of 2017, the second-largest footwear B2C e-commerce site in the United States, Shoes.com (second to Zappos.com, a subsidiary of Amazon), closed under intense market competition. Walmart’s Shoebuy immediately purchased the website domain.

Similar cases occurred across the U.S. vertical e-commerce market over the past two years. Since the beginning of the second half of 2015, numerous headlines announced big vertical e-commerce businesses being sold or disbanded:

In 2015, the United States’ second largest pharmacy group Walgreens closed its biggest online pharmacy drugstore.com;

British Hut Group managed to acquire Skincare.com, the largest online beauty retail in U.S., from Walgreens with help from KKR and other seasoned private equity firms;

The largest fashion flash-sale Gilt.com was taken over by Hudson’s Bay to become a part of its online business;

The biggest flash-sale dealer for mom & baby products, Zulily.com, was sold to QVC;

Fastest growing e-commerce business Jet.com was sold to Walmart for $ 3 billion just three years since its birth;

Recently, Amazon shut down a series of vertical e-commerce sites: Diapers.com, Soap.com, Pet.com;

There are some takeovers happening in the less influential vertical markets. E.g. Samsonite acquired ebags.com earlier this month.

The U.S. e-commerce market in the past two years are featured with Amazon being in the dominating position and the synergies that came along. On the other hand, the market was under heavy influence of the Matthew Effect. Amazon’s dominant market influence is based on strong traffic convergence, innovation, R&D capability and continuous investment in improving user experience. Apart from the U.S. market, Amazon is also active globally, introducing new retail formats to global customers.

Being the biggest and one of the most aggressive e-commerce group in the U.S., Amazon is leading the U.S. e-commerce market towards capital-centric and technology-driven competition, where medium and small players are merging to form stronger forces.

The last vertical e-commerce ‘fusion’ happened during 2004-2009, a period between Internet bubble recovery (2001) and global subprime mortgage crisis (2009). Most of the sites closed or sold were established after 2009, and a few (led by Drugstore.com and Quidsi sites) that had survived the earlier round of M&A frenzy. These e-commerce sites are featured with new business models, talented team and better vitality. But still, facing ‘omnipotent’ competitors such as Amazon, they cannot avoid the fate of being sold or closed.

Unlike ‘fusion’ state in the U.S., China’s cross-border e-commerce market is in the state of ‘fission’.

China’s cross-border e-commerce import started around 2014, and it is now in the state of wild and rapid growth like the U.S. during 2004 to 2009. As a vertical market, cross-border import e-commerce is not dominated by any key player.

Cross-border import adopters have different kinds of background, such as policy-driven opportunists, global retailers, new and classic marketplaces, traditional cross-country traders and more. Their influence was amplified under the ongoing consumption upgrade among Chinese middle class citizens.

Cross-border policy, expensive traffic acquisition cost and fragmentation of traffic are threats to the cross-border import e-commerce players. This is very close to U.S. e-commerce market during 2004 to 2009, when customer traffic was insufficient, and e-commerce businesses required external fund to supports growth. Furthermore, most of the businesses were operating in the red, and they lacked innovative business models.

The next two years will be crucial to cross-border e-commerce importers in China, as we learn from the history that 3-5 key players will emerge with different business models. How can businesses compete?

Competitions will be focused on building stronger, managed and credible supply chain capacity;

Healthy cash flow will be crucial to support E2E business, and they could come from self-raised capital, credit or cross-border supply chain finance solutions;

Deep investment in technology;

Continuous improvement of customer shopping experience;

Wide range of categories and products available for customers;

Take business to omni-channel